A Picture of London for 1802; being a Correct Guide to all the Curiosities, Amusements ,Exhibitions ,Public Establishments and remarkable Objects in and near London with a Collection of Appropriate Tables of the use of Strangers , Foreigners and all Persons who are not Intimately Acquainted with the British Metropolis by R Phillips.

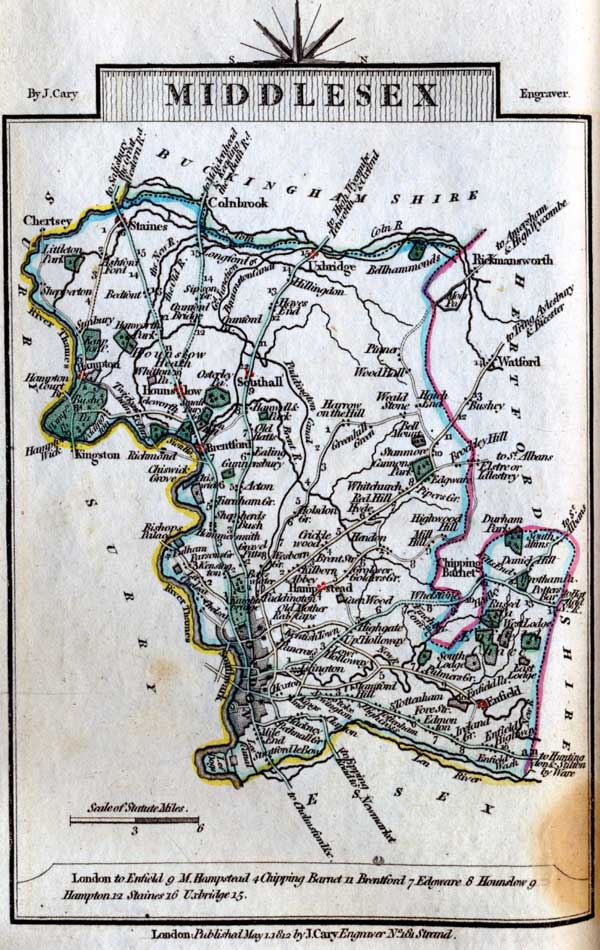

LONDON is situated in the latitude of 51 degrees 31 minutes north; at the distance of 500 miles south-west of Copenhagen; 190 west of Amsterdam; 660 north-west of Vienna; 225 northwest of Paris; 690 north-east of Madrid; 750 north-west of Rome; and 1500 north-west of Constantinople.

It extends, from west to east, along the banks of the river Thames; at the distance of 60 miles from the sea. It consists of three principal divisions; the city of London; the city of Westminster; and the borough of Southwark, with their respective suburbs. The two former divisions are situated on the northern side of the Thames, in the county of Middlesex, great part of them lying on hills, and forming a grand and beautiful amphitheatre round the water; the latter, on the southern bank, in the county of Surry, on level ground, antiently an entire morass.

The length of London is about seven miles, exclusive of houses that on each side line the principal roads to the distance of several miles in every direction: the breadth is irregular; being, at the narrowest part, not more than two miles; and, at the broadest, almost four miles. The soil is chiefly a bed of gravel, in many places mixed with clay. The air and climate are neither so constant nor temperate as in some other parts of the world; yet London is, perhaps, the most healthy city of Europe, from a variety of circumstances we shall have occasion soon to notice. The tide in the river flows 15 miles higher than London; but the water is not salt in any part of the town, and it is naturally very sweet and pure. The river is secured in its channels by embankments, where it does not touch the foot of the hills. When it is not swelled by the tide or rains, the river is not more than a quarter of a mile broad, nor in general more than 12 feet in depth; at spring tides it rises 12, and sometimes 14 feet above this level, and its breadth is increased to something more than a quarter of a mile. The principal streets are wide and airy; and exceed every thing in Europe, for the convenience of trade, and for the accommodation of passengers of every description: they are paved in the middle, for carriages, with large stones, in a very compact manner, forming a small convexity to pass the water off by channels; and at each side is a broad level path, formed of flags, raised a little above the center, for the convenience of foot passengers. Underneath the pavement, are large vaulted channels called sewers, which communicate with each house by smaller ones, and with every street by convenient openings and gratings, to carry off all filth that can be conveyed in that manner, into the river. All mud or other rubbish that accumulates on the surface of the streets is taken away by persona employed by the public for the purpose. London does not excel in the number of buildings celebrated for grandeur or beauty; but in all the principal streets, this metropolis is distinguished by an appearance of neatness and comfort. Most of the great streets appropriated to shops for retail trade, have an unrivalled aspect of wealth and splendor. The shops themselves are handsomely fitted up, and decorated with taste ; but the manufactures with which they are stored form their chief ornament. London abounds with markets, warehouses, and shops, for all articles of necessity or pleasure ; and, perhaps, there is no town in which an inhabitant who possesses the universal medium of exchange, can be so freely supplied as here with the produce of nature or art from every quarter of the globe.

Most of the houses in London are built on a uniform plan. They consist of three or four stories above ground, with one under the level of the streets, containing the kitchens. In each story is a large room in front, and in the back is a small room, and the space occupied by the staircase. Water is conveyed, three times a week, into almost every house, by leaden pipes, and preserved in cisterns or tubs, in such quantities, that the inhabitants have a constant and even lavish supply. Nothing can be more commodious or cleanly than the interior of the houses; and this character extends generally to lodging-hotels, taverns, coffee-houses, and other like places.

London is less populous, for its extent, than many other great cities. The streets are wider, and the inhabitants of every class, below the highest rank, enjoy more room for themselves and families than is usual for the same classes in foreign countries; not only she merchant, the wealthy trader, and persons in liberal employments, occupy each an entire house, but most shopkeepers of the middling class, and some even of the lowest, have their houses to themselves; and from all these circumstances his plain, that a given number of people is spread over a larger space in London, than in most foreign cities. Every mode of calculating she inhabitants of London is uncertain, and the result varies, in different hands, from 600,000 to 1,200,000. A comparison of the various calculations, and an examination of their data, induce us to state the population at 800,000. Those who think the honour of London affected by taking the population at a lower number than the popular opinion, will recollect, that it is creditable to the manners of the country, and the equity of the laws, that the middling and lower classes in London occupy the extent of ground that is ascribed to them by our calculation

Use the "Show me" link to locate London on the map. You may need to scroll down to see London highlighted.

|

|

| Quotations |

Chapter 15 Chapter 15

"Yes, for I am unable to keep my engagement with you. Mrs. Smith has this morning exercised the privilege of riches upon a poor dependant cousin, by sending me on business to London." |

Chapter 16 Chapter 16

After a short silence which succeeded the first surprise and inquiries of meeting, Marianne asked Edward if he came directly from London. No, he had been in Devonshire a fortnight. |

Chapter 17 Chapter 17

"What magnificent orders would travel from this family to London," said Edward, "in such an event!" |

Chapter 19 Chapter 19

He said so repeatedly; other things he said too, which marked the turn of his feelings and gave the lie to his actions. He had no pleasure at Norland; |

Chapter 24 Chapter 24

"But I only go for the sake of seeing Edward. He will be there in February; otherwise London would have no charms for me, I have not spirits for it." |

Chapter 25 Chapter 25

Whatever Marianne was desirous of her mother would be eager to promote -- she could not expect to influence the latter to cautiousness of conduct in an affair respecting which she had never been able to inspire her with distrust; and she dared not explain the motive of her own disinclination for going to London. |

Chapter 26 Chapter 26

Elinor could not find herself in the carriage with Mrs. Jennings, and beginning a journey to London under her protection, and as her guest, without wondering at her own situation, |

Chapter 27 Chapter 27

In the country, an unpremeditated dance was very allowable; but in London, where the reputation of elegance was more important and less easily attained, it was risking too much. |

Chapter 31 Chapter 31

Elinor, unable herself to determine whether it were better for Marianne to be in London or at Barton, offered no counsel of her own except of patience till their mother's wishes could be known; |

Chapter 32 Chapter 32

Design could never bring them in each other's way: negligence could never leave them exposed to a surprise; and chance had less in its favour in the crowd of London than even in the retirement of Barton. |

Chapter 35 Chapter 35

Edward was the first to speak, and it was to notice Marianne's altered looks, and express his fear of her not finding London agree with her. |

Chapter 36 Chapter 36

"And I protest, if I had any money to spare, I should buy a little land and build one myself, within a short distance of London. |

Chapter 40 Chapter 40

"Mrs. Jennings told me," said he, "that you wished to speak to me, at least I understood her so -- or I certainly should not have intruded on you in such a manner; though, at the same time, I should have been extremely sorry to leave London without seeing you and your sister;"

|

Chapter 42 Chapter 42

Marianne, few as had been her hours of comfort in London, and eager as she had long been to quit it, could not, when it came to the point, bid adieu to the house in which she had for the last time enjoyed those hopes and that confidence in Willoughby, |

Chapter 43 Chapter 43

"But she must not go round by London," cried Marianne, in the same hurried manner, "I shall never see her, if she goes by London." |

Chapter 44 Chapter 44

"Yes -- I left London this morning at eight o'clock, and the only ten minutes I have spent out of my chaise since that time, procured me a nuncheon at Marlborough." |

Chapter 47 Chapter 47

She had heard nothing of him since her leaving London, nothing new of his plans, nothing certain even of his present abode. |

Chapter 48 Chapter 48

Elinor flattered herself that some one of their connections in London would write to them to announce the event, and give farther particulars; |

Chapter 49 Chapter 49

How long it had been carrying on between them, however, he was equally at a loss with herself to make out; for at Oxford, where he had remained by choice ever since his quitting London |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 15

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 17

Chapter 19

Chapter 19

Chapter 24

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 27

Chapter 31

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 32

Chapter 35

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 36

Chapter 40

Chapter 40

Chapter 42

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 44

Chapter 47

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 49